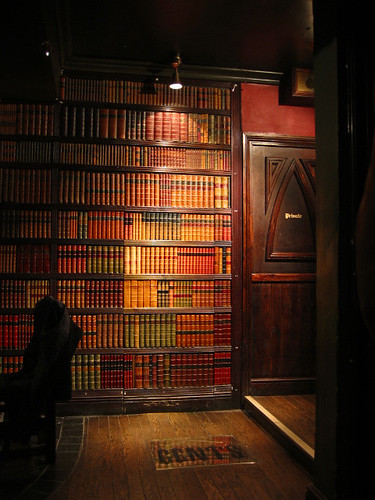

{Photo by rocketlass.}

A critic can feel he's done his job well when he sends you back to a favorite author, inspired by and armed with fresh insight. Jeremy at Readin has done just that with a recent series of brief, thoughtful posts on a series of lectures delivered by Borges in the 1970s; Borges fans should start here, then scroll through the next couple of weeks of Jeremy's posts.

He's sent me back to Borges's Seven Nights (1980), which collects seven lectures delivered by Borges in Buenos Aires in 1977; given my preoccupation with dreams, I turned immediately to the lecture on nightmares. While family commitments will keep me from writing a full post this weekend, I want at least to share this passage, in which Borges simultaneously conveys and analyzes the creepiness of a particular nightmare:

I remember a certain nightmare I had. It took place, I know, on the Calle Serrano, I think at the corner of Serrano and Soler. It did not look like Serrano and Soler--the landscape was quite different--but I knew that I was on the old Calle Serrano in the Palermo district. I met a friend, a friend I do not know; I saw him, and he was much changed. I had never seen his face before, but I knew his face could not be like that. He was much changed, and very sad. His face was marked by troubles, by illness, perhaps by guilt. e had his right hand inside his jacket. I couldn't see the hand, which he kept hidden over his heart. I embraced him and felt that I had to help him. "But, my poor Fulano, what has happened? How changed you are?" "Yes," he answered, "I am much changed." Slowly, he withdrew his hand. I could see that it was the claw of a bird.There's so much to like here: the dream itself; the dream-language description of the friend as "a friend I do not know"; and, most interesting, Borges's easy isolation of the self-deceiving role of surprise in dreams, and its relationship to the tug between expectation and surprise in external narrative. I'll be thinking about this--and about ghost stories--when I head to bed tonight.

The strange thing is that from the beginning the man had his hand hidden. Without knowing it, I had paved the way for that invention: that the man had the claw of a bird and that I would see the terrible change, the terrible misfortune, that he was turning into a bird. It also happens in dreams that are not nightmares: they ask us something, and we don't know how to answer; they give us the answer, and we are astonished. The answer may be absurd, but in the dream it is exactly right. Everything has been prepared. I have come to the conclusion, though it may not be scientific, that dreams are the most ancient aesthetic activity.

Wow, thanks -- that's great to know that I sent you back to Borges. I've been meaning to look up Seven Nights.

ReplyDeleteSpeaking of nightmare, a beautiful couple of lines from Bolaño's "Ghost of Edna Lieberman":

And Gilberto Owen?

Have you read him?

say your lips without sound,

says your breath

and your blood that circulates

like the beam of a lighthouse.

But her eyes are the lighthouse

piercing your silence.

Her eyes like the ideal

geography book:

maps of pure nightmare.